In the early hours of June 14th 1941, NKVD employees knocked on the doors of hundreds of homes all across Estonia. The awoken families scarcely knew what they were accused of when officials read them the decree on the basis of which they would be arrested and deported from their homeland.

People were given a few hours to gather their belongings – they were allowed to bring up to a 100kg of items – and then were transported by trucks to railway stations, where trains consisting of cattle cars awaited them. All together there were 490 wagons specifically brought for this purpose which were located in Tallinn, Haapsalu, Keila, Tamsalu, Narva, Petseri, Valga, Tartu and Jõgeva. Adult men were placed in trains marked A, while women, children and the elderly were placed in wagons marked B. For the majority of the men, that morning would be the last time they ever saw the rest of their families.

Initially, the A and B cars traveled together in one convoy, but after some time, the first cars were detached, and the men were sent to forced labor camps in Ukraine, Sverdlovsk, and Kirov Oblasts. The majority of the imprisoned men died within the first months due to inhumane conditions in mines, forest works, or road construction; many were killed outright. By the spring of 1942, only a couple of hundred men out of approximately 3,500 sent to labour camps remained alive.

The women and children in B wagons were resettled to remote villages across various parts of rustic Siberia. After 5-6 years, children with families in Estonia were allowed to return. However, between 1941-1951 state security apparatus found most of those children and sent them back to Siberia during the next wave of deportations. Most of the deportees managed to return to their homeland only after Stalin’s death during the late 1950s.

A decree that came from Moscow on June 13the 1941 foresaw the deportation of 11,102 people but some of them were warned and managed to hide, resulting in “only” around 10,000 people being deported. According to various estimates around 6000 of them perished during first few years in exile. There are no exact numbers how many people eventually managed to return to their homeland.

The Wagon of Tears

The June deportations are commemorated every year in Tallinn through a thematic installation:

Video testimonials

This video is in Estonian but has English subtitles.

One of many tragic fates

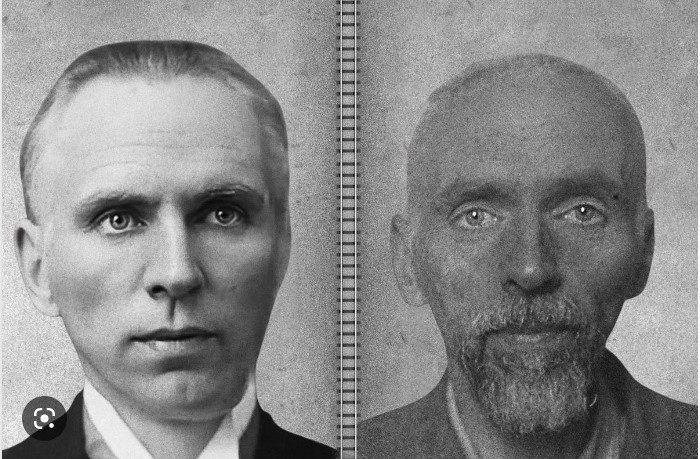

Foto: Eesti Ekspress

Entrepreneur Joakim Puhk and his family’s tragic story through never before seen documents, letters and photos.

On June 17, 1941, the 9 trains carrying deportees, began leaving Estonia via Narva and Irboska. Each railway car held more than 50 people. The overcrowded wagons received only a narrow sliver of light through a small opening. There was no water available, and a pipe running through the floor served as a toilet. The air inside the cars was heavy and stale; under the scorching sun, the wagons became unbearably hot. An interior view of such railway cars can be seen in the permanent exhibition at Vabamu.

From the Vabamu collections

Below is one of the many stories preserved through letters and photographs in the collections of Vabamu.

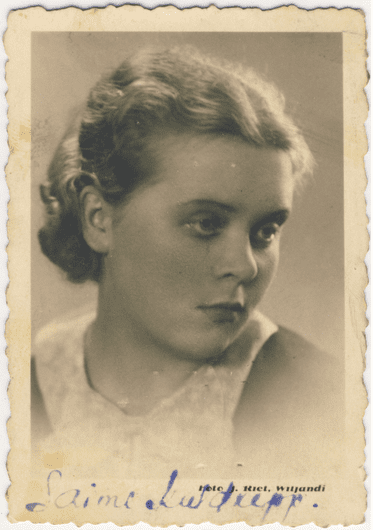

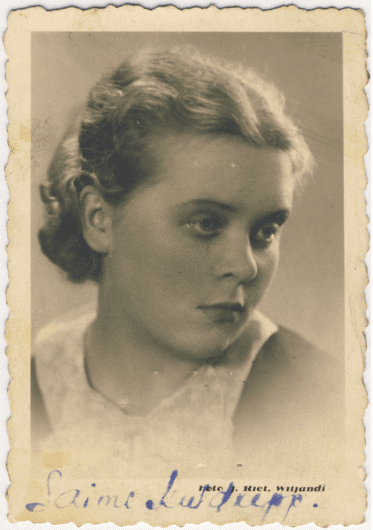

Aleksandra aka Saima Kuldkepp (1914-?) and Leida Lindre (1915-1993) were classmates in Kaansoo primary school in Pärnu County.

Saima was from a large farm and was deported in June 1941 together with her parents to the village of Sborny in the Tchainsky District of Tomski Oblast. She was not released until June 1958. From Siberia, Saima sent letters to her former classmate Leida, in which she described the hardships of her daily life and expressed a deep longing for her homeland.

Among other things, Saima sent her classmate a photo of herself from Siberia, which had been taken in Viljandi in 1937. Written on the back of the photo is:

“To Jaan! If you like, you can look at it from time to time too – 29.12.1937 – From Sanna.”

The photographer is unknown.

Leida herself was imprisoned during autumn 1950 because while working in a local grocery store she had fed the forest brothers – a local partisan group fighting against Soviet occupation – living nearby. After being arrested she spent several years in Narva prison.

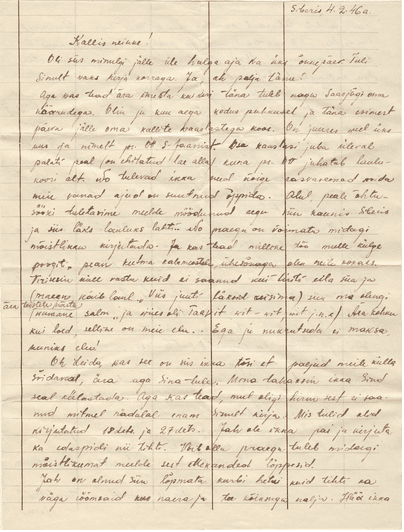

A letter dated February 4, 1946, begins on a cheerful note. Saima thanks her pen pal for her two previous letters and mentions having recently spent a month on home leave, during which she was able to reunite with old friends for the first time. She then goes on to describes activities at the camp and notes that the weather is extremely cold: -55 degrees Celsius.

Saima goes on to describe her new job as a cook for fishermen, which she admits is not a pleasant position. She writes: “I got released from hard labor, but they found a cook was needed, and after pressuring the foreman, they found me yet another job I could do.”

Saima asks whether it’s true that she’s planning to come visit her, but adds that Leida shouldn’t come, as she’d rather meet her in Estonia. Saima also mentions that since she hadn’t received any letters from Leida for several weeks, she became worried and asks her to continue writing as often as before.

She writes that there have been an endless amount of sad moments, but also joyful times filled with laughter and jokes. It is good to have cheerful companions who help keep your spirits up. Moods change quickly, she says, but there is still something to be happy about. Toward the end of the letter, Saima says it was truly wonderful to be home with her mother again after such a long time and that she is still in good health. To conclude, she says that Leida should write to her about anything at all, because every word is a joy to read. She passes on many greetings.

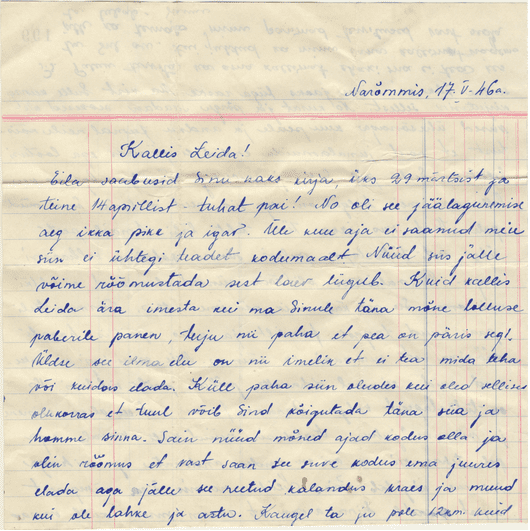

In a letter dated May 17, 1946, Saima begins by mentioning that she received two letters yesterday. For over a month, she had not received any news from her homeland. She describes being in low spirits and says she doesn’t know what to do or how to go on living.

She then mentions that on May 1st, an Estonian girl married a local collective farm worker. All the wedding guests were locals – none of her own people. The young man had returned from the front just a few months ago, and it had happened quickly.

Saima says she feels sorry for the girl and hopes it was the first and last time something like this happens. As for herself, she says she would rather die an old maid.

Saima believes her only companion will be water, with which she hopes to live in harmony. She describes traveling on the Ob River, which is over two kilometers wide, and hearing the waves speak strange voices and words to her. Her companions laughed at her, but she enjoyed the feeling immensely.

The letter also reveals Saima’s pain at Anton no longer writing to her. Additionally, her mother’s complaints are difficult for her to bear. Near the end of the letter, she shares instructions on how to remove excess water from crops without damaging them.

At the end Saima dreams if only there was Leida and someone else from her former life with her. She asks not to forget her as she’s all alone in a far away land.

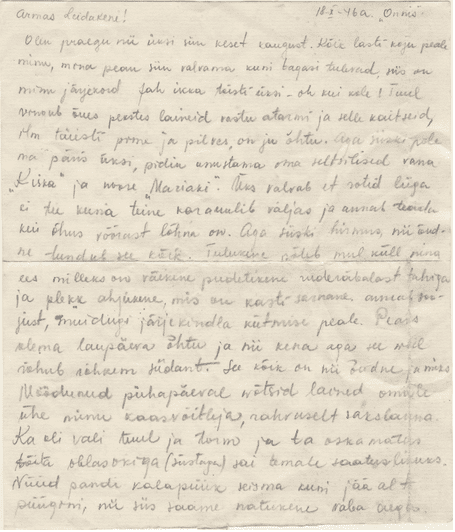

Saima’s third letter from a Siberian “hut” to her former classmate Leida is dated October 18, 1946.

Saima writes that she is alone in far away place. Everyone else were allowed home- only she has to stay behind and keep watch until the others return, and the weather is extremely unpleasant. She does mention, however, that she is not entirely alone: she has two companions, an old cat named Kiska and a young dog named Mariaki. One keeps the rats at bay, and the other alerts her if there’s an unfamiliar scent in the air.

Everything else, though, is frightening and terrible. The previous Sunday, stormy waves claimed the life of one of her German comrades, who died due to his inability to handle a kayak.

Saima then says that she now has a bit of free time, as fishing has been suspended until ice fishing season begins. The nature around her is actually quite beautiful, she admits, but there’s nothing to do, and being all on her own is terrible. She’s sent word to her mother, asking her to come and keep her company. She also describes the meal she has just finished preparing and speculates on what kind of weather might be coming next.

Saima believes this will be the last letter she’ll be able to send by boat, as the dreadful time is approaching again when no post arrives. At the end of the letter, she says that the routine and monotony of life are driving her mad. It’s nothing but eating, working, and sleeping. She feels like she’s losing her mind.