There were around 600 exhibits in the the Museum of Occupations when it was first opened in 2003, the current permanent exhibition only displays 140 exhibits. The collections of Vabamu now include more than 40 000 items, most of which will never be displayed. Yet each item has a background story why it ended up in the collection. More important than the artefact itself is the narrative that surrounds it.

When the creation of the Museum was announced in the beginning of 2000s, people were eager to donate the items they had treasured in their families for generations. Exhibits were also acquired from antique stores and flea markets. It has become less frequent these days for people to just walk into the building carrying an item they want to donate to the Museum. If it does happen, the collection manager will interview the person who wants to donate the objects: who was the previous owner of the item(s), how did they obtain it and what other information they might have about the object(s). The Museum has a policy of no reimbursement for donating items to the Museum.

When the item has been accepted to the collections, both the Museum and the donor will have to sign a legal document of receipt. The collection manager will then measure and describe the object, take a picture or scan it and upload the information to the Museum database Entu which is accessible to the public in Estonian only. The Museum collections are kept in a storage unit in Kristiine subdistrict in Tallinn.

It is up to the curators of exhibitions to decide what items are elected for temporary exhibitions. Some items are occasionally displayed on the social media accounts of the Museum but most of the objects never make it to the public eye. This online exhibition displays a few items that have never before been on display but have made an impact on the current and former employees of the Museum – Aive, Kristjan, Sander and Martin.

Items for display

A Mug

This one-of-a-kind kitchen utensil was the first ever item to be uploaded to the museum database Entu, carrying a code 000001/000. This mug was built out of a Swiss coffee jar for boiling tea in Zhezdi labour prison. The first known owner was the forest brother Harald Kivilo who had been convicted for treason in 1957 for 25+5 years of prison. When he was released in 1985 or 86, he left the the mug in the prison and the next owners were Artur Pupart, Arvo Pesti, Aldar Raskazov and Jan Kõrb. The latter brought the mug along with him as he was released and gave it to Heiki Ahonen in 1988 in Munich, Germany.

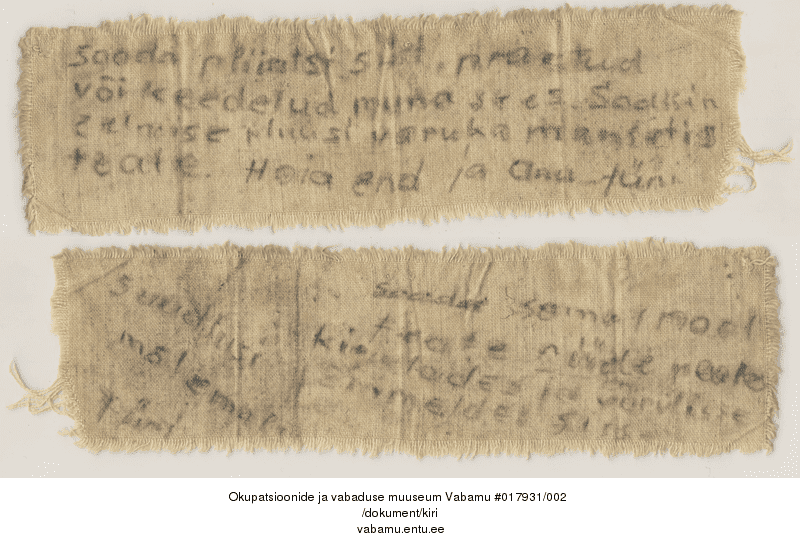

Letters from prison on pieces of cloth

The writing on the textile says: “I will keep sending these messages on pieces of cloth, sewing them into the lining. Kisses to both of you, Jüri.”, “Send charcoal for writing inside a boiled or a fried egg. I sent a message inside the cuff of the previous shirt. Stay safe and watch out for Anu. Jüri.” These are messages sent by Hans Pilvar from a prison on Nunne street to the laundry in 1947. Hans Pilvar had been a sports instructor who was active in Self Defence. He was arrested on April 15th 1947 in Tallinn and convicted two months later according to §58-1a and §58-11, i.e in treason and being a public enemy. He received 10+5 years of prison in Dzhezkazgan copper mining labour camp in Karaganda Region in Kazakhstan. He was released in March of 1956 and died in Estonia in 1981.

Iron Cross of the Third Reich, 2nd class, with a ribbon

These Iron Crosses accompanied by several documents and phographs were donated to the Museum by Anna Reyner whose father Eduard Simson had graduated from Estonian Military Academy and drafted to the German Army in the II World War where he served on the front. Eduard Simson left Estonia with the retreating German forces and moved on to the United States. He graduated from Stanford University and later defended his PhD in Pshychology at Heidelberg University. For the rest of his life he worked as a clinical psychologist in several different clinical institutions across the US and lectured at universities.

Phonograph from the ashes

Tallinn was heavily bombed by the Soviet air forces in March 1944 that left big part of the city in ruins. People went looking for things to capture from these ruins and somebody found a Russian phonograph horn that was attached to a German-made (either ABB or AEG) motor. The wooden box must have been rebuilt later and the phonograph was used to play records in 1950s in a community center in Käesalu, a village in Harju County in North-Western Estonia.

Posters from different occupations

Although representing different occupations – German and Soviet -, these posters carry similar visual and contextual propaganda elements. Both occupations stress the importance of national pride and resistance to war through patriotic visuals.

Enn Põldroos, a visual artist, has said that the Soviet poster art was aiming at photographic resemblance and embedded a never-ending battle between the artist and the editor. The artists were constantly trying to find the loopholes in censorship and sometimes they succeeded. Poster art offered an opportunity for the artists to try something new, to apply Western style that might have gone unnoticed by their audiences.

1st pair

- German Occupation:

“A Road to Freedom 22nd of June 1941“ – a poster to praise German occupation. A soldier on the foreground is carrying a swastika flag while the others on the background carry the flags of “liberated” nationalities, including the Estonian tricolore. The poster has been ripped from the left corner.

2. Soviet Occupation:

“We will not tolerate war!”, Estonian National Publisher 1951. The authors are well-known artists Siima Škop and Aino Bach.

2nd pair

- German Occupation:

“Hitler, the Savior!”, Offsetdruck Carl Werner Reichenbach IV. 1940s.

2. Soviet Occupation:

“Thank you, Big Stalin for our happy childhood!”, Estonian National Publisher 1952. The author is a well-known book illustrator Siima Škop.

3rd pair

- German Occupation:

“Collective effort for our homeland. I’m on the front line, you are on the home front.” R. Tohver & Ko. 1940s.

2. Soviet Occupation:

“… and you became a blossoming social country for the sun to shine down on you.” A line from the national anthem of Estonian Socialist Republic. Tallinn 1962.

Letters of the Lindermann Brothers

In 2013 there was a exhibition in the Museum of Occupations about forest brothers. After walking through the exhibition, a lady came to the curator and said she recognized her uncles on one of the pictures and that she has a box full of their letters from prisons. A few weeks later the Museum received a box that contained 138 letters, as well as postcards and documents sent from various labor camps across the time span of 15 years.

Arnold and Johannes Lindermann were forest brothers who were convicted for treason in 1957 for 25+5 years, they were released in 1972 and 1974 and died in Estonia in 1989 and 1984.

One of the folders contains detailed descriptions of their family history, deportations, living in the forests; there is a close account of Arnold Lindermann being shot by “the special guns of the punitive troops”; there’s also a draft for a letter to the ESSR’s top government institutions; questions on deportations/destructions; drafts for pleas of pardon. Last pages of the folder have been removed.

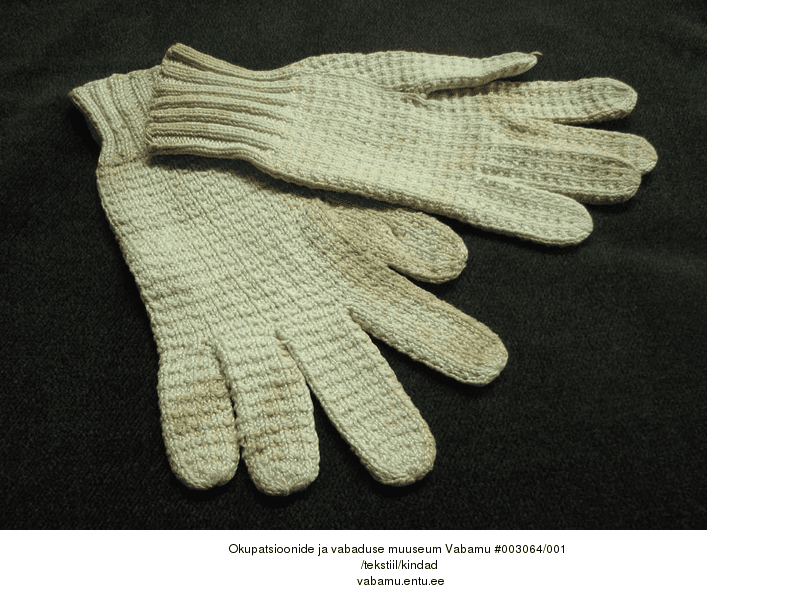

White Gloves of the Nuremberg Judge

Richard Dillard Dixon was appointed in 1947 to serve as an alternate to any of the Tribunal judges of the Nuremberg war crime trials. He left his gloves to the car of his driver Vello Karuks, an Estonian emigre. Karuks later lived in the US and became an active member of the Estonian community in Seattle where he also became good friends with the Kistler family. Many people involved in the early days of the Kistler-Ritso Foundation consider him to be one of the key figures in the birth of the Museum of Occupations. Unfortunately he passed away just a few months before the opening of the Museum.

The Nuremberg trials were a series of military tribunals held by the Allied forces under international law and the laws of war after World War II. The trials were most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, judicial and economic leadership of Nazi Germany, who planned, carried out, or otherwise participated in the Holocaust and other war crimes.